News Story

Spread Hope: The "Smart Bra"

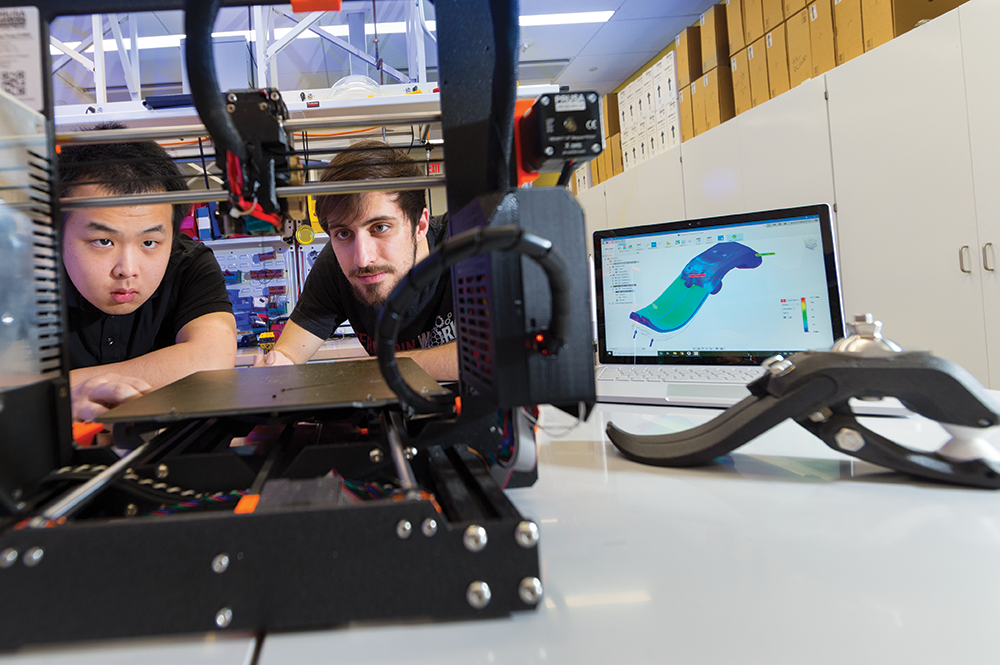

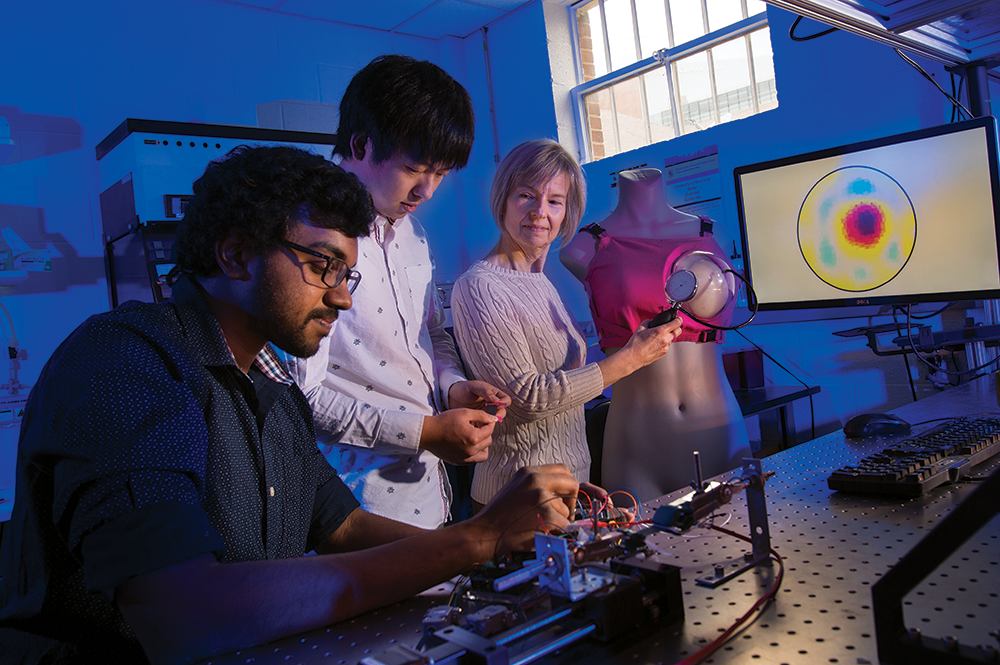

From left to right: Master's student Rahul Subramonian Bama, undergraduate Hudson Ye, and Professor Elisabeth Smela with their "smart bra." Photo: John T. Consoli

In the winter of Hudson Ye’s freshman year, he logged onto the Clark School’s website with a mission: compile a list of faculty with whom he wanted to work. At the top of that list was Professor Elisabeth Smela, and for good reason; Smela has amassed about 100 journal articles, including three in Science, holds 10 patents, and was a Jefferson Science Fellow, Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) recipient, and UMD Woman of Influence.

What Ye didn’t know was that Smela, along with Professors Hugh Bruck and Miao Yu, had just landed Mpact Challenge funding for their “smart bra,” a low-cost wearable device that could conceivably detect breast cancer early enough for treatment. And while they had just filled their team of graduate students, the Mpact funding gave Smela the flexibility to add the tenacious Ye to the project.

The project concept was particularly meaningful to Ye; his grandfather had died of lung cancer after a late stage IV diagnosis.

“I wanted to help out and also learn,” says Ye. “And I managed to get in.”

The idea for the smart bra stemmed from an innovative material developed by Smela, Bruck, and Yu: a polymer enveloping thin layers of graphite to create a stretchable, electrically conductive composite. While the team initially considered using it for tactile sensing in robots, a chance meeting at a conference sent them in an unexpected direction.

“A colleague said to us, ‘Have you ever thought to use this to detect breast cancer?’” says Smela. “He was working with a doctor in India who had too many patients and too few trained medical personnel. He needed a tool that could be used to triage the patients who came in as a first line of detection.”

“... I don’t know if I’d get this opportunity at another university.”

In many countries in the developing world, breast cancer has a low-incidence rate, resulting in a lack of awareness among patients and trained professionals in medical settings. When patients do present, they are often at stage IV or V and can no longer be treated. So the team set their sights on a two-centimeter lump with the stiffness of a pencil eraser, which roughly equates to treatable stage II breast cancer. The design works similarly to manual palpation, applying pressure to the chest like a blood pressure cuff to detect resistance changes produced by denser tumor tissue. It offers the familiarity of a bra, with a lower cost and higher accessibility than traditional diagnostics.

While simple in concept, it is complex in execution, requiring knowledge spanning a number of disciplines and substantial trial and error. At any given time, the lab has students working on robotics, materials, programming, electronics, and mechanics. Ye has worked on the project for two years, later recruiting a second undergraduate student, Shirley Shi, who is an electrical engineer with a talent for sewing.

“No matter the level, there is no one who can just land here and know it all,” says Smela. “The undergrads, like everyone else, are learning. But they bring an excitement, a willingness to learn, an ability to lead, creative ideas, and persistence.”

And while “doing something that matters” drives Ye each day in the lab, it’s the chance to work with Smela that he cites as the biggest reward.

“It’s an amazing experience and I’ve learned so much, not just the research but also how to apply what I’m learning in the classroom and how to ask the right questions,” says Ye. “She’s so accomplished in her career, and that’s something I want to achieve in the future. Being able to work with her all the time, I don’t know if I’d get this opportunity at another university.”

“He’s marvelous,” says Smela. “Experimental research is difficult. It’s discouraging. You keep failing. Those with the ability to show up fresh every day and give it another shot, with a new idea or with just more care, are the personalities that will persist.”

Read more about the Mpact Challenge projects.

Published March 15, 2020