No article found or not published for this site.

Recent Stories

Stories / Mar 2, 2026

Celebrating Women’s History Month & Multiracial Heritage...

Stories / Feb 26, 2026

Gupta Receives Multiple Honors

Stories / Feb 16, 2026

Agonafer Wins Top Prize for Data Center Cooling Proposal

Stories / Feb 5, 2026

Celebrating Black History Month 2026

Stories / Feb 4, 2026

Engineering is a Family Affair

Stories / Jan 27, 2026

Maryland Engineering Maintains Status as National Leader in...

Stories / Jan 15, 2026

Groth Appointed CRR Director

Stories / Jan 15, 2026

The Lasting Legacy of George Dieter, 1928-2020

Stories / Dec 19, 2025

Dankowicz: Positioning ME for the Future

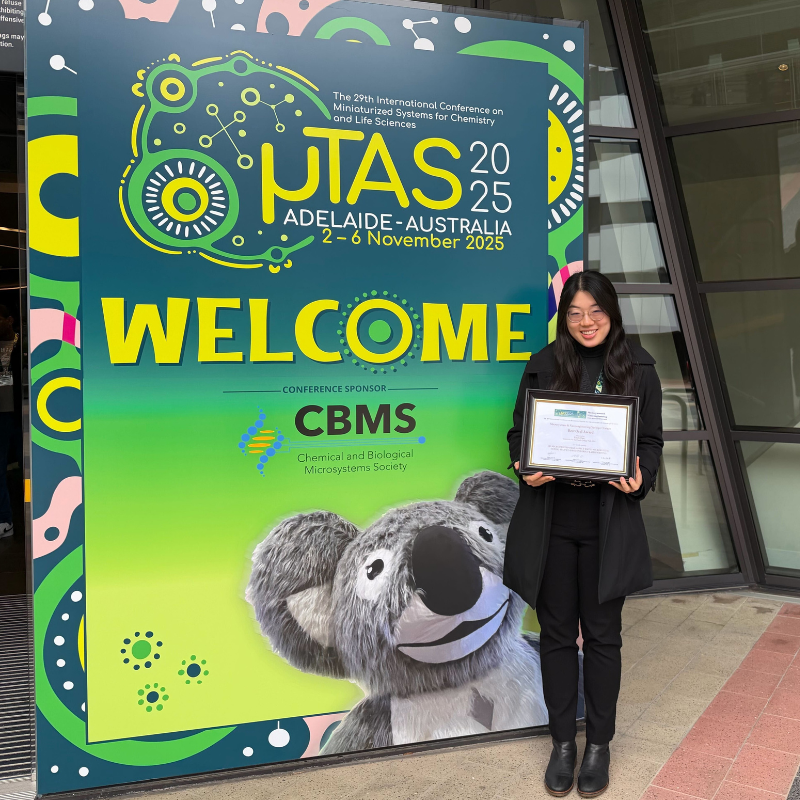

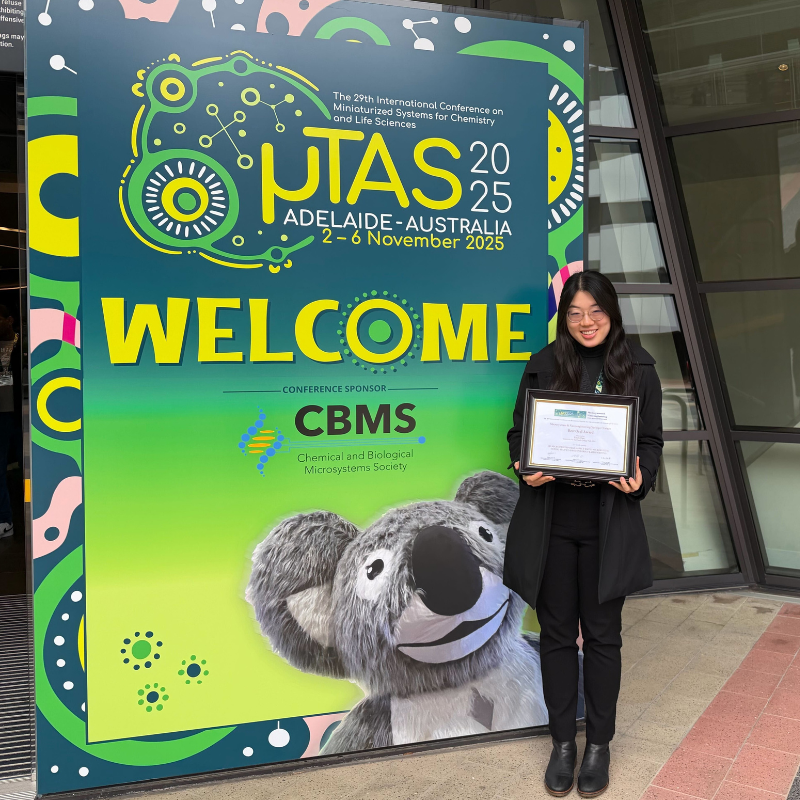

Stories / Dec 4, 2025

Tian Honored with Oral Presentation Award at MicroTAS 2025